An Experience of Synchronous On-Line Classes

Universidad Nebrija

mgenis@nebrija.es , mmartinl@nebrija.es

RESUMEN

La metodología del Máster en Enseñanza Bilingüe de la Universidad Nebrija incluye un conjunto de herramientas de aprendizaje con el objetivo de facilitar la adquisición de diversas destrezas, entre las que destacan las lingüísticas. Como parte de un método activo, el estudiante se convierte en el protagonista de su propio aprendizaje, y el profesor - experto en su campo - en el conocedor de los mejores medios para trasmitir el conocimiento y ayudar a los alumnos a mejorar sus estrategias de aprendizaje.

La enseñanza se realiza a través de una metodología mixta (blended learning), combinando clases presenciales y tele-presenciales a través del campus virtual, plataforma colaborativa donde se unifican espacios típicos del aprendizaje en línea, tales como los foros, las conversaciones en línea o chats, los enlaces, los buzones de tareas, documentos, etc.

El aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera a distancia es una difícil tarea. Sin embargo, la interacción en tiempo real apoyada por un sistema de gestión asíncrona puede convertirse en una herramienta fundamental para asistir al alumno. La herramienta de videoconferencia Blackboard Collaborate constituye la verdadera novedad de este proyecto. Se trata de una herramienta de comunicación síncrona en línea con la que estudiantes y profesores pueden trabajar conjuntamente en tiempo real en sesiones virtuales. De forma asíncrona, los estudiantes pueden completar tareas y tests de autoevaluación, comunicarse con los profesores y compañeros, e incluso visionar las sesiones grabadas que hayan podido perder.

Nuestro artículo tiene como objetivo presentar y describir las herramientas empleadas usando esta metodología en el Máster cuyo propósito es el de proporcionar a los estudiantes unas oportunidades efectivas de aprendizaje de contenidos y lengua extranjera. El contenido de este artículo servirá además de base para futuras investigaciones sobre la adecuación de la metodología al mencionado programa.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje mixto, aprendizaje síncrono, adquisición de lenguas extranjeras, aprendizaje activo interacción en tiempo real, plataforma virtual colaborativa

ABSTRACT

The M. A. in Bilingual Education at Nebrija University includes a diverse set of training tools which aims to facilitate the acquisition of various skills, among which language skills are the most important ones. As part of an active teaching method, the student is the protagonist of his own learning and the teacher is the expert in the field, the connoisseur of the best means to transmit knowledge and to help students improve their learning strategies.

The teaching methodology used is blended learning, combining face-to-face and online classes through the virtual campus, a collaborative platform which makes use of typical e-learning educational spaces such as fora, chats, links, task box, documents, etc.

Learning a second language at a distance is a very difficult task. However, live interaction supported by asynchronous learning systems can be crucial tools to aid the student. The tool Blackboard Collaborate constitutes the real novelty in the project. Through this on-line synchronous tool teachers and students can work together in real time in virtual classrooms. Asynchronically, students can complete assignments and self-evaluation tests online, communicate with their teachers and fellow students, or even view recorded classes that they might have missed.

Our article aims at presenting and describing the tools used at the M.A. programme whose objective is providing students with effective content and foreign learning opportunities. The content of this article will also serve as the basis for future research about the adequacy of the method for the referred programme.

Keywords: Blended learning, synchronous learning, foreign language acquisition, active learning, live interaction, collaborative virtual platform

1. Introduction

After the initial enthusiastic years of e-learning, it was decided that it did not meet all the expectations. E-learning was said to involve a lot of disadvantages when compared with traditional face-to-face teaching. The low motivation of the students, the dropouts and the lack of feeling of being part of a learning community were among the main objections. Thus, several years ago, the term blended learning was coined to fill in some of the gaps left by e-learning.

Blended learning refers to a type of approach in which two, or even more, learning environments and activities are combined. The most typical type of blended learning brings together face-to-face teaching with on-line learning in order to create a collaborative space where synchronous and asynchronous interaction among peers and with teachers takes place.

Educational blends can offer a lot of advantages, not being the least important one that they save money, but they also meet the students' learning needs regarding time, mobility and studying style, giving multiple opportunities of interaction to a diverse population of learners.

In this article we analyze the main reasons to implement a blended learning methodology as well as its principle features. We also explore the different tools available at the blended learning model employed at the M.A. in Bilingual Education at Nebrija University, which aims at providing students effective content and foreign learning opportunities. The content of this article will also serve as basis for future research about the efficiency of using this methodology within the referred programme.

2. Theoretical background

The improvement of Internet connection in the 90s, allowed network learning, which was defined as

However, the concept of networking was first mentioned by Illich (1971, online) who declared,

In this century, Brown (2002, p. 3) highlighted the fact that the Web is a medium that "honors multiple forms of intelligence-abstract, textual, visual, musical, social, and kinesthetic", so learners can choose their way of learning, what has been called multiple intelligences by Gardner (1983), and that kids in our digital age learn in a different way, describing them by four dimensional shifts: (a) literacy now involves many types of texts and genres and skill to process them; (b) learning is now infotainment, i.e. information mixed with entertainment; (c) bricolage, i.e. the capacity of finding something "an object, tool, document, a piece of code-and to use it to build something you deem important." (Brown 2002, p. 5); and (d) tendency toward action, i.e. learning by doing. Brown (2002, p. 8) also coined the term learning ecology to refer to "an open, complex, adaptive system comprising elements that are dynamic and interdependent".

George Siemens (2006, Preface, p vii) stated that knowledge had changed from hierarchies to networks and ecologies, considering that "concepts relate to other concepts but not in a linear manner". And that "learning (defined as knowledge patterns on which we can act) can reside outside of ourselves (within an organization or a database), is focused on connecting specialized information sets. The connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing." (Siemens 2006, p. 30).

More recently, Andrews (2011) states that e-learning has altered the very character of learning, first because e-communities are essentially different from any other community of knowledge; second, because it enlarges the possibilities of learning as regards to space, time and resources; third, because it has altered the nature of knowledge itself, being now seen as dynamic, i.e. incessantly developing and changing; and fourth because it transforms the conceptual and semiotic resources of the individual, producing new outputs, i.e. new knowledge. Andrews (2011, p. 120) concludes that

A pedagogical approach between fully face-to-face courses and fully on-line courses appeared around the turn of the century. Along the years, this approach has been called blended, mixed, hybrid, integrated, flexible, multi-method, b-learning. Blended learning methodology rests on the idea that several teaching models are combined by using different types of virtual or physical resources. Nowadays, the term has narrowed its meaning to denote the teaching design that uses technology along with face-to-face classes. Although this meant a positive change in pedagogical practices, many online courses entailed only asynchronous content delivery complemented with face-to-face tutorials. But, as So and Bonk (2010, p. 1) argue,

With the significant movement toward blended learning during the past decade, the concept of face-to-face classes has evolved to include synchronous interaction mediated by any web management system, such as Moodle or Blackboard Collaborate. This blend has proved very successful, as it provides daily opportunities for students to discuss information and clarify doubts among them or with the help of the teacher. It also fosters collaboration among students, building a sense of being part of a learning community. Blended learning approaches which integrate the two modes of interaction, i.e. synchronous communication and asynchronous communication, thus, are gaining interest, but it is far more interesting to combine face-to-face with virtual communication, which offers benefits such as dynamic interaction among participants, immediate feedback, exchange of different viewpoints, personal involvement, collective construction of knowledge along with conveniently programmed time from any place the student chooses to be.

Hrastinski (2008) examined synchronous communication and asynchronous communication, distinguishing between what he calls personal participation and cognitive participation, and concluding that synchronous communication increased the students' motivation and complemented asynchronous communication which "provides increased reflection and ability to process information." (Hrastinski 2008, p. 505).

This hybrid modality is an eclectic approach oriented towards critical thinking, collaboration and knowledge construction as key elements. Blended learning rests mainly upon the well-established constructivist and cognitivist theories, and on the emerging trend of connectivism.

Constructivism considers the individual mental process when learners are interacting with the medium. In this sense, learners are not objects of learning but active subjects of learning. These theories were also influenced by humanistic approaches which mainly pay attention to individual differences, different rhythms and learning styles.

One of the key principles in blended learning is its transformative potential and the community it can create. Connection with others is essential to realize a community of enquiry. As Garrison & Kanuka (2004, p. 99) claim, within this methodology, students learn to accept their responsibility in knowledge construction. According to them, "a sense of community is also necessary to sustain educational experiences overtime". Therefore, by combining synchronous oral and written communication within a learning community, blended learning can progressively support "higher levels of learning through critical discourse and reflective thinking." (Garrison & Kanuka 2004, p. 98).

Recently, learning has acquired a new dimension with virtual learning environments where knowledge is understood as a process which occurs within an ever-changing environment (Siemens 2005). Connectivism allows us to understand and redesign knowledge relations within the new learning contexts. For this theory, learning is a process of network formation, similar to the way our neurons and computers are connected to transfer information. A network contains nodes and connections. Nodes can be human but they can also be data-bases, libraries, organizations, that is, any source of information. Therefore, under this view, the possibilities for establishing connections are infinite; knowledge and learning will depend on diverse opinions and information sources and on the application to real-life situations; the purpose of learning activities will be to update information continuously; maintaining connections will be necessary to facilitate continuous and life-long learning.

Connectivism acknowledges that learning lies in a collectivity of individual opinions and considers connections (and not contents) as the starting point for learning. For that reason, it requires a new teaching methodology, where instead of designing courses, learning environments are designed for the students to collaborate in other people´s knowledge construction, through social learning networks, in order to search and create their own network of nodes based on their own interests and needs.

Blended learning represents an emerging trend in higher education. Society and technology alter the way in which we communicate and learn, and this inevitably alters as well the way we think. Forms of communication and our ability to manage information challenge our cognitive abilities and the traditional classroom paradigm. In traditional teaching, the transmission is a key issue. In the new paradigm, there is a holistic approach to teaching and learning, further ahead from the sheer transmission of information.

3. Blended-Learning Methodology

Internet and ICT tools were first introduced in educational contexts as additional material to enhance face-to-face learning. Soon, these tools were used as learning platforms for pure technology-mediated distance tuition, digital learning or simply, on-line (distance) learning.

Historically, face-to-face teaching and on-line instruction have been separated because of the media available and the instructional methods that could be used in each instance. Digital learning is considered distributional, meaning that the same information can be equally effectively delivered to a greater audience. Distributed learning contexts emphasize the interaction between learners and materials, whereas face-to-face contexts prioritize human to human interaction (Bonk and Graham 2004).

However, distributed learning environments are increasingly taking on a place which was previously only reserved for face-to-face ones. In this sense, human interaction is for example also possible through "computer-supported collaboration, virtual communities, instant messaging, blogging, etc." (Bonk and Graham 2004, p. 20).

Blended learning can be distinguished from other online-enhanced classroom or fully on-line learning experiences. Blends are both simple and complex. At its simplest they are the thoughtful integration of classroom face-to-face learning with online experiences. At the same time, they are very complex as in there is a limitless design possibilities in their implementation and application. Either way, it represents the integration of the two main components but not just by adding online resource to face-to-face tuition. A blended learning design represents a reconceptualization and reorganization of the teaching and learning dynamic, in order to give solution to various specific contextual needs (Rossett and Vaughan 2006).

However, there is not a standard way about how to blend, in what proportion and with which tools. Different institutions do it in different ways depending on their needs, expertise and resources (Bonk & Graham 2004). They can occur at different organizational levels: for a specific activity, for a whole course, for an entire programme or at an institutional level. The last two levels can be usually chosen by learners, while the first two are often prescribed by instructors.

Depending on the proportion in which the two methodologies occur, different blends can be found. Some blends enable learning, as they intend to provide an additional flexibility. Others can enhance learning since they offer supplementary materials online to core learning experiences. And finally, others can transform learning in the sense that learners are no longer receivers of information but active constructors of their own learning through interaction in the new media (Bonk and Graham 2006).

As no blend is identical to other, hundreds of definitions can be met. For instance, according to Thorne (2003, p. 18), it is "the right learning at the right time and in the right place for every individual". For Bonk and Graham (2004, p. 18), on the other hand, blended learning is a "pedagogical approach that combines the effectiveness and socialization opportunities of the classroom with the technologically enhanced active learning possibilities of the online environment". And Garrison and Vaughan (2008, p. 14) claim that it is "an opportunity to fundamentally redesign how we approach teaching and learning in ways that higher education institutions may benefit from increased effectiveness, convenience and efficiency".

3.1. Elements in Blended Learning

Notwithstanding that all blends are different we can draw some common elements which are present to a more or lesser extent in all of them (Alcides Parra 2008; Bartolomé 2008; Bonk & Graham 2004).

a) On-campus and on-line sessions, in which teachers and students socialize and interact in flexible groupings. A global approach to knowledge is given, key study aspects are suggested, opinions are exchanged and argued, and acquired knowledge is applied to new contexts. Besides, during these classes, teachers provide students with the necessary work guidance and motivation by generating group dynamics, holding group tutorials, and supervising individual and group activities.

b) Independent activities, through which autonomous learning is fostered. Learners actively acquire knowledge mediated by texts and digital materials. For Bartolomé (2008) the use of resources in an independent way is one of the greatest contributions of Internet, in either of the forms that independent activities may adopt: simulations, tutorials, cases, problems or exercises.

c) Practical activities, which are usually carried out in face-to-face classes, in the shape of tutorials and simulations. Students learn by doing and they have contact with real experiences.

d) Communication tools, used to favour synchronous and asynchronous interaction between all participants in the learning process. They can take the form of fora, chats, distribution lists, group mails, webquests, blogs, wikis, videoconferences... Previously, communication tools were very dependent on written communication, where non-verbal communication was completely lost. Group dynamics through Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) could not be compared to in-campus group cohesion. However, virtual discussions over video- and audio-conferences are progressively gaining path to the traditional chats or fora as real interactive communication tools.

e) Assessment procedures, which can provide students with quantitative as well as quantitative data. They also foster students´ follow up through formative evaluation, allowing learners to check their own progress and receive feedback of activities and tests. Evaluative elements can be traditional, through personal interviews, small groups sessions, class-group sessions; or new, based on multiple-choice tests, collaborative work, critical thinking assignments, frequently-asked questions, questions in the fora, inquiries through e-mails, etc.

f) Virtualized contents, which are formatted in such a way that they can be virtually transmitted, in accordance with the digital resources available. They must also be in close relation to the subject objectives and students´ expectations. Contents are supplemented by other digital contents, like audiovisual youtube and podcasts, textual pdf files, or hypertextual web pages. This way, students are offered information in diverse formats in order to cater for the needs of different students.

g) Collaborative group work, which can help students develop interpersonal, intercultural, social and civic competences. In blended learning, students must be flexible and positive, and adapt themselves to manage and use these technologies. Therefore they must actively participate in the learning and teaching process by planning and organizing their time effectively, collaborating in group work, providing their ideas and knowledge to the group through the fora, chats and in all the proposed activities (Bartolomé 2008).

h) Tutors, who are the facilitators of all the knowledge which integrates the course. From a technical and organizational point of view, tutors must transmit confidence in the technology being used so that students can focus exclusively on the course. They must also prepare the course agenda and procedures, including all the different interactions between teachers and students, students among themselves, or class group with other experts. Besides, they must evaluate the students´ achievement, and discover their attitudes and perceptions. From a social perspective, tutors have to create a friendly environment in order to increase group cohesion, they must foster group work, welcome students to participate in the course and hold regular, respectful and attentive communication with them (Garrison & Vaughan 2008).

4. Blended-learning at Nebrija University

Nebrija University began experimenting with blended learning a decade ago, with a Masters course for SFL (Spanish as a Foreign Language) teachers who had full-time jobs or family responsibilities during the day, and could not attend face-to-face classes. The program, grounded on a pedagogical model in which the student is the real protagonist of the learning process, mixes face-to-face classroom learning with guided and independent work in the virtual campus. The interaction among participants, i.e. students, teachers and tutors, rely on discussion, task and project fora which expand the in-campus classroom activity, which takes place twice a year within an intense two week period, with the aim of minimizing the isolation feeling of the on-line student.

With this background, the Master in Bilingual Education was launched adding to the asynchronous type of on-line learning already in use, the on-line synchronous interactive tools, where teacher and students come together at the same time in a live virtual event. The Bilingual Master, thus, uses Nebrija Virtual Campus along with in-campus classes every two Saturdays, so as to not interfere with the students' work or duties, complemented with synchronous two-hour tutorials from Monday to Thursday every week.

5. Master´s Degree in Bilingual Education

Bilingual programmes have progressively become a reality in Spanish state schools in the last decades. The Master in Bilingual Education course in Nebrija University aims at giving answer to this great social demand by providing future bilingual teachers with the required background knowledge and teaching skills to perform their duties in the newly-created Primary and Secondary schools.

The course deals with the linguistic theories behind bilingual education as well as the different pedagogical models implemented in Spain. It also considers the implications that a bilingual syllabus has on the organization of the teachers' team and on the classroom management.

The overall objective of the Master is the comprehensive training of school teachers (Early Childhood, Primary and Secondary Education) that use English as the vehicle for content teaching. Such training, therefore, involves, firstly, that teachers acquire the linguistic, pragmatic and cultural competence of English at CEFR level C1, necessary to their profession, with particular emphasis on active oral and written skills, and secondly, that the teachers understand the theoretical, conceptual and methodological contents of bilingual education and its practical application in the classroom.

5.1. On-line Classes

On-line classes can be easily accessed through the virtual campus and run through the platform Blackboard Collaborate with direct access through the virtual campus.

The on-line classes for every subject are held every two weeks on weekdays, except in the case of the subjects to train specifically English communicative skills which are taught weekly.

On-line classes are two-hours long and they are delivered in small groups with a maximum of twelve students through synchronous videoconference. During these sessions teachers review the main contents, students raise their questions and some practical activities are proposed.

These classes have several characteristics to point out: (a) they are scheduled in the late afternoons so that students can easily combine their studies with other activities; (b) they can be attended from any place with the only requisite of access to internet; (c) they allow real-time communication between teachers and students and students among themselves; and (d) since these classes occur in real-time, they are very interactive and collaborative. To this regards, it is important to note that, during on-line sessions, all participants: 1) can speak and listen to each other though the headphones and the microphone; 2) can communicate at any moment with each other through written messages on the chat; 3) can view each other through the webcam; 4) can share their desktops, documents, presentations, audio- and video-files; 5) can record sessions, which can be easily accessed at a later time for revision or in case of absence to classes; 6) can visit websites together; 7) can write collaboratively on the whiteboard using different slides, which can also be saved for future use; and 8) can work collaboratively, in reduced groups, at the breakout rooms created by the teacher and use the same tools as in the main room. Teachers can access all these rooms at any moment and interact with the students. Students can share their work, findings and conclusions with the rest of the class when they are sent back to the main room by showing the slide they have shared at the breakout room.

5.2. On-campus Classes

These sessions are held in campus during weekends once a month, except in the case of the subjects to train specifically English communicative skills which are taught every two weeks. These sessions are seventy-five minutes long (one hour and forty-five minutes for English communication skills).

On-campus classes are delivered with the whole group of students. During these sessions students have the chance of solving problems, applying what they have learnt to practical situations, as well as raising questions still unsolved.

These classes offer the following features: (a) they are scheduled on Saturday mornings every fortnight so that students can combine their studies with other activities; (b) they are delivered in-campus with all kinds of material and ICT resources and facilities; (c) they are interactive and collaborative. Besides, since they occur face-to-face, collaboration between the teacher and the students, and the students among themselves is guaranteed.

Other significant in-campus activities are the two immersion periods (called "Immersion Weeks") at the end of both semesters and after the ordinary examination periods. During these days (four in each term) students attend many different practical workshops related to teaching methodology.

5.3. Virtual Campus Tools

Nebrija University campus tools are used for asynchronous on-line learning mode. Students can access the virtual campus and its tools whenever they wish. There is a virtual campus for every subject and for every group. Hereby we show a list of the available tools as well as a description of their functionalities.

A) Documents.

In the Documents section teachers upload the subject syllabus, the group arrangement for the subject, the contents, the activities and any other relevant document (additional readings, annexes, etc.) related to each unit in the corresponding unit folder. The date of the documents uploading is visible to students to clarify the access to the necessary files. Students can easily download and print out all these documents.

B) Links.

In the Links section, teachers upload any interesting and relevant website related to the field of each subject. Each link can be accompanied by a comment and be placed in different folders, in order to provide a clearer access to information.

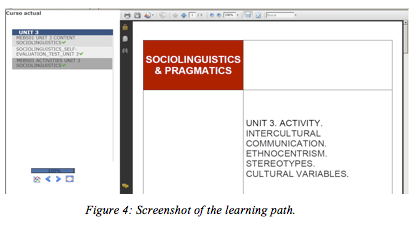

C) Learning Path.

Every unit has a Learning Path which guides students through their learning process. Here students access all the documents and exercises regarding each unit in a specific order to guarantee the progressive acquisition of knowledge. Students can also go backwards and forward whenever necessary to revise information. And they can view at all times their own progression for every unit through the percentage bar. Thanks to this tool teachers can check in which stage their students are at any given moment as well.

D) Task Box.

Through this tool students send their activities to teachers and receive their corrected activities from teachers. The system records the date and the time when both students and teachers exchange their files, in order to facilitate control of students´ work and teachers´ feedback. The system does not allow rejecting activities past the deadline. Teachers receive a direct link to the students´ activities, and students receive a link to the teachers´ corrections directly on their e-mail addresses.

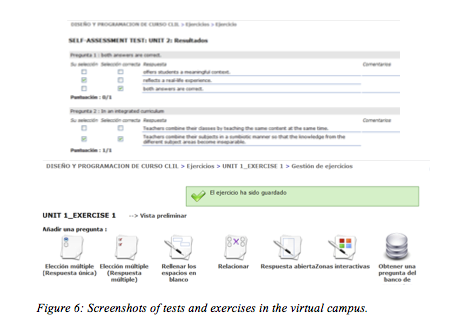

E) Self-Assessment Tests & Exercises.

Teachers can create self-assessment exercises and tests in different formats (multiple choice, cloze, gap-filling, relating, open-ended and interactive questions) depending on the nature of the exercise. Students can check themselves their level of achievement, the correct answers and clarifying comments to each questions made by teachers. The system allows these exercises to be done only once or several times, depending on the objective the teacher intends with each exercise. For every unit there is a self-evaluation test which students can do as many times as they need.

F) Agenda.

In the Agenda, teachers communicate to students important dates regarding classes, deadlines, exams, etc.

G) Bulletin Board.

Through this tool teachers communicate the students any important and clarifying information as regards classes, changes in dates, activities, etc. Students receive notifications on the bulletin board directly to their e-mail addresses.

H) Groupings.

Here both teachers and students can view names and e-mail addresses of participants in their groups, so that they can contact each other when necessary. Teachers can also organize students in groups for on-line learners´ collaborative work.

I) Forum.

In the Forum, both students and teachers can communicate asynchronically. In the Forum teachers and students´ photographs are visible so that social bonds are reinforced. Both can create thread about topics, raise questions, make comments and share ideas. Since these comments are visible to everyone, this tool allows collaborative learning. However, within the Forum there is a "Private Questions" zone where teachers and students can address each other to communicate about more particular matters.

J) Chat.

Nebrija´s chat is a tool open to all Nebrija University educational community. In the chat participants can easily find each other through the directory of the course they are taking, or through the department directory. This chat also offers the advantage of letting participants talk synchronically through voice tools, or interact through written messages, in a similar way than tools as Skype. But this chat offers another great innovation: participants can open a videoconference like the one described in point a. in this section and work collaboratively and with access to all the tools already existing in their online classes through videoconferences.

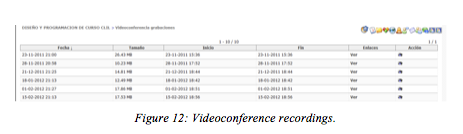

K) Videoconferences & Recordings.

Students attend the on-line classes described through an external link, accessible from and outside the virtual campus. Through the link Recordings students will find a list of the recorded sessions with the dates and times so that they are quickly found. All sessions are recorded in order to allow students revise contents and activities done during class time, and also to be able to view it for the first time in case they have been absent. The system allows to stop or pause the recording as well as to go forward and backwards.

6. conclusions

Nowadays, blended learning methodology seems to be a must in all the institutions for higher education, as it is a flexible model with a student center approach that allows each participant to follow their own pace and choose the appropriate strategies according to their needs and learning style. Group and individual work, diverse materials and tools and the role of the teacher as facilitator are other assets that can make this instructional system effective.

However, the design of the course has to be appropriate in order to stimulate learners and foster meaningful learning. This is best done if synchronous (face-to-face and virtual) and asynchronous communication are carefully brought together, so as to encourage interaction and give support and feedback during the learning process. In this sense, the blended learning design available at the M.A. in Bilingual Education at Nebrija University seem to be able to offer students new learning possibilities and tools to increase both their content and foreign language learning. Future research on the area will determine whether or not this innovative methodology is considered affective for the referred programme.

Alcides Parra, L. (2008). Blended learning, la nueva formación en educación superior. AVANCES Investigación en Ingeniería, vol. 9, pp. 95-102. Available at http://www.revistaavances.co/47 (accessed 28 June 2012).

Andrews, R. (2011). Does e-learning require a new theory of learning? Some initial thoughts. Journal for Educational Research Online, vol. 3 (1), pp. 104-121. Available at http://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2011/4684/pdf/JERO_2011_1_Andrews_Does_e_learning_require_a_new_theory_S104_D_A.pdf (accessed 20 June 2012).

Bartolomé, A. (2008). Entornos de aprendizaje mixto en educación superior. AIESAD RIED, vol. 11 (1), pp. 15-51. Available at www.utpl.edu.ec/ried/ (accessed 21 May 2012).

Bonk, C. & Graham, C. (2006). Blended learning systems: definition, current trends, and future direction. In C. J. Bonk & C.R. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs, pp. 1-21. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer Publishing.

Brown, J. S. (2002). Growing up digital: how the web changes work, education, and the ways people learn. United States Distance Learning Association, vol. 16 (2). Available at http://www.usdla.org/html/journal/FEB02_Issue/article01.html (accessed 23 June 2012).

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Garrison, R. & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Elsevier Internet and Higher Education, vol. 7 (2), pp. 95-105. Available at www.sciencedirect.com (accessed 22 June 2012).

Garrison, R. & Vaughan, N. (2008). Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles and Guidelines. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Goodyear, P. M., Banks, S., Hodgson, V. & McConnell, D. (Eds.). (2004). Advances in Research on Networked Learning. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hrastinski, S. (2008). The potential of synchronous communication to enhance participation in on-line discussions: a case study of two e-learning courses. Information & Management, vol. 45 (7), pp. 499-506. Available at

http://www.journals.elsevier.com/information-and-management (accessed 16 June 2012).

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling Society. New York: Harper and Row. Available at

http://ournature.org/~novembre/illich/1970_deschooling.html (accessed 15 December 2012)

Nebrija University. 2009. Introducción a Dokeos. Available at

http://wiki.nebrija.es/wiki/Introducción_a_Dokeos (accessed 15 May 2012).

Nebrija University. 2011. Herramientas básicas de Dokeos. Available at

http://wiki.nebrija.es/wiki/Herramientas_básicas_de_Dokeos (accessed 20 June 2012).

Nebrija University. 2012. Herramientas avanzadas de Dokeos. Available at

http://wiki.nebrija.es/wiki/Herramientas_avanzadas_de_Dokeos (accessed 18 May 2012).

Rossett, A. & Vaughan, R. (2006). Blended learning opportunities. American Management Association, pp. 1-27. Available at

http://www.grossmont.edu/don.dean/pkms_ddean/ET795A/WhitePaper_BlendLearn.pdf (accessed 10 May 2012).

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: a learning theory for the digital age. International Journal for Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, vol. 2 (1), pp. 3-10. Available at

http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm (accessed 30 May 2012)

Siemens, G. (2006). Knowing Knowledge. Online: Creative Commons. Available at

http://www.elearnspace.org/KnowingKnowledge_LowRes.pdf (accessed 20 June 2012).

So, H. J. & Bonk, C.J. (2010). Examining the roles of blended learning approaches in computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) environments: a Delphi study. Educational Technology & Society, vol. 13 (3), pp. 189-200. Available at

http://www.ifets.info/journals/13_3/17.pdf (accessed 9 September 2012).

Thorne, K. (2003). Blended Learning: How to Integrate Online and Traditional Learning. London: Kogan Page Publishers.