Pragmatic awareness of conversational implicatures and the usefulness of explicit instruction

La comprensión de implicaturas conversacionales y los beneficios de la instrucción explícita

Universidad Nacional del Litoral (Argentina)

lcignetti@fcv.unl.edu.ar , sdigiuseppe@fcjs.unl.edu.ar

RESUMEN

El presente estudio se propone investigar el grado de comprensión de de implicaturas conversacionales por parte de estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera y si la instrucción explícita facilita la interpretación de las mismas. Para tal fin, veintiséis estudiantes fueron asignados a un grupo experimental y a un grupo de control. Se utilizó una evaluación escrita de opción múltiple para medir su desempeño antes y después de la intervención. El análisis de los resultados indicó que la mayoría de los estudiantes en ambos grupos demostraron ser poco sensibles a las implicaturas previo al período de instucción. Sin embargo, al finalizar dicho período, los estudiantes del grupo experimental realizaron un avance significativo en lo que respecta a la interpretación de implicaturas.

Palabras clave: implicatura conversacional, comprensión, instrucción explícita.

ABSTRACT

The present study attempts to investigate the degree of pragmatic awareness of learners of English as a foreing language and also whether explicit instruction facilitates the learners’ interpretation of these implicatures. For this purpose, twenty-six students were assigned to an experimental and control group and their performance was measured through a written multiple-choice test before and after the treatment. The analysis of the data indicated that most students in both groups proved to be rather insensitive to implicatures before instruction. However, after being exposed to explicit teaching, the students in the experimental group exhibited a significant improvement in their recovery of implicatures.

Keywords: conversational implicature, awareness, explicit instruction

Fecha de recepción: 4/9/2015

Fecha de aceptación: 9/9/2015

1. INTRODUCTION

In our everyday communication we do not merely encode what we think in words, but our intentionality is also reflected through the linguistic choices that we make. Thus, in order to arrive at the intended message, it is not sufficient to draw its meaning from the language itself. We must also, and more importantly, work out what the sender wants to convey through it. When the literal meaning of what speakers say does not coincide with what they intend to communicate, listeners rely on a set of principles to infer indirect meaning. Given the pervasiveness of this inferencing process, which Grice coined conversational implicature, in our daily interaction (Green, 1989 as cited in Bouton, 1994), it is undeniable that this strategy is highly significant in interpreting and conveying a message in a conversation. Also, it has been claimed that the principles resorted to in the interpretation of implicatures can operate differently across societies (Keenan, 1976 as cited in Bouton, 1994), among different social groups and situations (Leech, 1983) and therefore pose an obstacle to cross-cultural communication.

Bouton’s cross-sectional study (1988) on the interpretation of implicatures in English by nonnative speakers with the same language proficiency and different first language (L1) cultural backgrounds in a second language (SL) context, rendered empirical evidence for the above-mentioned claim. He found out that their interpretations varied from those of the native speakers and also among themselves. Consequently, he discredited the influence of language proficiency and attributed the differences to their belonging to different cultures.

Due to the fact that these differences sometimes represent areas of difficulty, there is a need for pedagogical intervention in learners’ comprehension of the targeted pragmatic features. The review of interventional empirical pragmatic studies in Rose & Kasper (2001) has revealed the promising role of explicit instruction in pragmatics.

The findings in two studies on conversational implicatures support this idea. In a later study (1994), Bouton tested the teachability of implicatures and came to the conclusion that those implicatures which were difficult to recover through exposure benefited from explicit instruction. The other study that investigated the role of instruction in the interpretation of implicatures was conducted by Kubota (1995). She replicated Bouton’s study but did not arrive at the same conclusion. Rose & Kasper resort to length of treatment, language proficiency, learning environment and motivation to account for this dissimilarity. Kubota’s treatment was rather short in comparison with Bouton’s. The subjects in her study belonged to a foreign language (FL) context, whereas Bouton’s subjects were immersed in the target-language context and they were also more proficient and highly motivated than those in Kubota’s because the treatment included learning opportunities not only inside but also outside the classroom. There is no doubt that the English as a second language (ESL) subjects were at an advantageous position with respect to the English as a foreign language (EFL) subjects since FL learners are generally prone to encounter little target-language input or have few opportunities to produce the target language outside the class compared to learners immersed in SL environments (Rose & Kasper, 2001). Thus, the role of instruction becomes more important.

Instruction in pragmatics does not always aim at teaching new contents to learners, but it may be also directed at making students aware of their pragmatic knowledge base and urging them to use what they already know since when acquiring the pragmatics of a foreign language students do not tend to capitalise on their existing pragmatic knowledge and are often likely to interpret utterances literally, failing to exploit contextual information (Rose & Kasper, 2001).

The present study further explores the issues raised in Bouton and Kubota’s studies by addressing the question of whether Argentinian learners’ recovery of the implicit meaning triggered by English utterances in an EFL context can be problematic, and also of whether the learners’ ability to infer conversational implicatures can be facilitated by explicit instruction.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Approaching the notion of implicature

The salient contribution of the notion of implicature to pragmatics lies in the fact that it offers some explanations of how it is possible to convey meanings which are not directly expressed in words. The concept of implicature promises to bridge the gap between what is literally said and what is conveyed. How interlocutors cope with the indeterminacy of utterances is one salient issue in pragmatics since it attempts to systematically analyse how the receiver interprets the addresser’s intended, but sometimes underdetermined message (Levinson, 1983).

Grice (1975) coined the word conversational implicature to refer to the inferencing process by means of which the meanings of utterances are interpreted in relation to their context of use (Bouton, 1994).

When he describes how implicature works, Grice asserts that conversational implicatures are based on some general rules or maxims of conversational behaviour. These rules fall into what he labeled the Cooperative Principle (CP). It aims at guiding participants on using language efficiently and effectively and towards achieving cooperative goals. In other words, it assumes that people taking part in communication expect themselves and the others to be cooperative, that is, be truthful, be informative, be true, be relevant and be brief. It is this shared knowledge on the part of interlocutors that gives rise to conversational implicatures. The inferencing process through which implicatures arise results from either adhering to the maxims or deliberately infringing the maxims. According to Grice, the maxims are rational ways of interacting cooperatively rather than arbitrary conventions. He suggests that since interlocutors do not always uphold the maxims in communication, when they are faced with an apparent non-cooperative response, they will try to go beyond it on the assumption that the principle of cooperation is preserved (Levinson, 1983).

Grice meant the term implicature to differ from the literal meaning of the expressions and to cover all pragmatic inferences. He distinguishes conversational implicatures from conventional implicatures. The latter are inferences which, contrary to conversational implicatures, are strictly dependent on the use of certain lexical items and do not have to be retrieved from knowing the maxims that rule conversation (Levinson, 1983).

Bouton (1999) distinguishes two subsets within conversational implicatures according to their nature. Those implicatures which possess a systematic nature are known as formulaic implicatures, whereas those implicatures that do not have an inherent formula are labelled non-formulaic or idiosyncratic implicatures.

Within the first subset, he differentiates implicatures based on a structural formula from those based on a semantic formula. POPE Q, sequence-based implicatures and Minimum Requirement Rule are examples of the first group. In the POPE Q implicature a person answers a YES/NO question with another question. For the implicature to work the person asking the first question will understand the implicature if he/she knows that the answer to that question is the same as the answer to the second one and just as obvious. This kind of implicature is named after the prototypical rhetorical question, Is the Pope Catholic? Sequence-based implicatures result from the presence of the word and and are based on the idea that the order in which the events are expressed coincides with the order in which they occurred. Implicatures based on the Minimum Requirement Rule result from providing the addressee with the minimum amount of information needed for the conversation to continue. In other words, giving more information than is required would be redundant since it is not important for the conversation to go to know whether he/she possesses more of something and if he/she has less than expressed he/she would be lying. Indirect criticism and irony constitute the second group. Indirect criticism implicature is generally used in response to a request for an evaluation of something when the evaluation is negative. In order to avoid being rude or criticising directly, the speaker praises some unimportant feature of the item he/she has been asked to evaluate to imply that there is nothing else to be praised. Ironies are successfully decoded when, confronted with a blatantly false utterance and assuming that the speaker is being cooperative, the hearer searches for another meaning that differs from the actual words. This is how interlocutors arrive at the opposite, or negation, of what has been stated.

There is only one type of implicature in the second subset, namely relevance-based implicature. Since one expects a person’s contribution to a conversation to be relevant, when this does not seem to be the case the interlocutor looks for another new meaning beyond what is said, relevant to the particular conversation and its context.

2.2 The role of culture in the interpretation of implicature

It is interesting to note that the universality of the CP has not been sustained because it has been argued that the Gricean maxims do not operate in the same manner in all communities (Leech, 1983). The fact that they may be utilised differently across cultures could make people from one society misinterpret implicatures used by those from another one. That is to say, cultures differ in the way they implement these principles in context and also in what they consider to be cooperative (Rose & Kasper, 2002) and therefore the usefulness of implicature as a conversational strategy in cross-cultural communication can be diminished (Bouton, 1999). For instance, in his cross-sectional study, Bouton (1988) concluded that the international SL learners differed in their interpretation of implicatures with respect to the native speakers and among themselves. More precisely, out of the six culture groups under study he found out that the Latin Americans occupied the second nearest position with respect to the Americans, who were the target group (Bouton, 1988).

2.3 Grounds for the teaching of pragmatics

Interlanguage pragmatics research has mainly concentrated on the study of production rather than judgement and perception. Studies on judgement and perception examine the differences that may arise in L2 speech and written simulations between native speakers and learners which, in comparison with production studies, are not easily observable but equally important. They show that native speakers’ and learners’ judgements and perceptions often differ (Bardovi-Harlig 2001). Studies on perception also reveal valuable information on the types of utterances learners get as input and learners’ awareness of the similarities and differences between their mother tongue and the TL (Rose & Kasper, 2001).

Many of these studies have focused on FL learners because, compared to SL learners, they tend to receive less TL input or their chances to produce the TL outside the classroom are rather scarce. Moreover, learners do not always use their existing pragmatic knowledge in comparable TL situations and this also lends support to the inclusion of instruction in interlanguage pragmatics to raise their awareness of their available L1 knowledge and promote its use in TL contexts (Rose & Kasper, 2001).

In their review of empirical pragmatic studies on both production and comprehension, Rose & Kasper (2001) conclude that native speakers and SL learners exhibit marked differences in their pragmatic systems. These differences can sometimes be equated with areas of difficulty, which warrant pedagogical intervention in learners’ comprehension of the TL pragmatic aspects.

The need for instruction validates Schmidt’s (1993) Noticing Hypothesis which posits that awareness is necessary to make input into intake (Takahashi, 2001). In other words, linguistic features will become intake only if learners consciously notice them (Rose & Kasper, 2001). As Bardovi-Harlig puts it: “Without input, acquisition cannot take place…we owe it to learners to help them interpret indirect speech acts as in the case of implicatures” (2001: 31).

2.4 Determining factors in developing TL pragmatic competence

There are some factors that influence learners’ development of their TL pragmatic competence in an FL context.

2.4.1 L1 transfer

The keen interest in the influence of the first language and culture on TL learning can reflect the close connection between interlanguage and crosscultural pragmatics studies (Bardovi-Harlig, 2001). Kasper (1997) describes this influence as pragmatic transfer which can be either positive or negative. Positive transfer takes place when the forms and functions in the L1 map onto the TL (Rose & Kasper, 2001). This leads to successful interactions, whereas when a correspondence between the two languages is wrongly assumed by learners, namely negative transfer, the outcome could be the use of non-target expressions or their avoidance (Bardovi-Harlig, 2001). In particular, adult learners can resort to their universal or L1-based pragmatic knowledge when acquiring FL pragmatics. Unluckily, learners do not always transfer their existing knowledge and strategies to TL contexts, and this is also the case for some pragmatic aspects (Rose & Kasper, 2001).

2.4.2 The learning environment

It seems that learners immersed in the TL culture are at an advantage with respect to those in an FL context. However, it does not follow that learners in an FL environment will not develop pragmatic competence (Niezgoda & Röver, 2001).

2.4.3 Pragmatic input

The availability of pragmatic input in instructional contexts also influences the development of pragmatic, which can be provided by means of teacher talk and/or materials. However, as often as not, textbooks cannot be trusted to provide reliable pragmatic input since this input is not always presented in a realistic and contextualised way to language students (Bardovi-Harlig, 2001). More precisely, Bouton (1990 as cited in Kubota, 1995) found that there are few examples of implicatures in ESL textbooks and they are not usually dealt with explicitly. Assisting learners with authentic input should be aimed at in pedagogy so as to attempt to reduce the pragmatic differences between learners and native speakers (Takahashi, 2001). By way of example, watching videos is an appealing way for learners to notice the TL area in natural discourse since it gives learners the chance to access and integrate sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic knowledge fast and efficiently (Tateyama, 2001).

2.4.4 TL proficiency

Even though it has been shown that grammatical competence and pragmatic competence do not necessarily coincide, it is still unknown to what extent grammatical competence limits the value of the input to the learner (Olshtain & Blum-Kulka, 1985; Bardovi-Harlig & Hartford, 1990; House, 1996; Bardovi-Harlig, 1999a, in Rose & Kasper, 2001). It seems that proficiency may have little influence on pragmatic competence and performance since the strategies used by learners at an intermediate and advanced level were found to be similar (Kasper & Schmidt, 1996, in Rose & Kasper, 2001). Even though none of the published studies have included low proficiency learners (Kasper, 1996; Kasper & Schmidt, 1996; Kasper & Rose, 1999, in Rose & Kasper, 2001), Rose & Kasper (2001) hypothesise that beginning language learners might not be able to use certain strategies due to their not having acquired sufficient linguistic knowledge.

2.4.5 Pragmatics instruction

Studies on the effect of instruction in pragmatics support the idea that explicit teaching is more effective in helping learners develop their TL pragmatic competence in comparison with implicit teaching or lack of instruction (Kasper, 2001; Takahashi, 2001; Tateyama, 2001; Yoshimi, 2001).

Rose & Kwai-fun (2001) compared the effect of deductive and inductive teaching in the development of pragmatic competence and they concluded that both types of instruction had a positive impact on developing pragmalinguistic proficiency; however, only the deductive instruction was effective in the acquisition of sociopragmatic features.

Testing also has an effect on interlanguage pragmatics. Undoubtedly, SL learners are at an advantage over FL learners since their learning success usually combines test results and success in communicating with native speakers. However, FL learners’ success is restricted to the outcomes of grammar-oriented tests (Bardovi-Harlig, 2001). Thus, the novel incorporation of pragmatics as a learning goal in the curricula will prove to be ineffective unless pragmatic ability is considered to be integral to language tests (Rose & Kasper, 2001).

2.5 Investigating implicature in cross-cultural communication

Within the few data-based interventional studies on interlanguage pragmatics, some authors have focused on how different classroom experiments impact on the acquisition of implicatures (Kasper, 2001).

Bouton conducted a series of studies on the interpretation of implicature. In a cross-sectional study (1986) he tested 436 nonnative speaking (NNS) students who belonged to six different culture groups. They had the same level of English proficiency and had just arrived in the USA. This study aimed at investigating whether their interpretation of implicatures in American English differed from that of 28 college educated American native speakers (NSs) (Bouton, 1988). The latter took the same test as the SL students and it consisted of a multiple-choice instrument. The results showed that NNS students arrived at the same interpretations of implicatures as the NSs only about 79% of the time. Bouton concluded that native speakers and SL learners with the same language proficiency and different L1 backgrounds differed in their interpretation of implicatures. Moreover, these differences were also found within the SL group. The different culture groups were arranged on a continuum which ranged from the NSs at one end to the People’s Republic of China on the other. The Germans, Latin Americans, Taiwan Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese occupied the middle positions in that order. On this basis, Bouton concluded that it seems unquestionable that people who belong to different cultures differ in their interpretation of at least some implicatures. Since he found that native speakers and SL learners with the same language proficiency and different L1 backgrounds differed in their interpretation of implicatures, he dismissed these differences as being due to their proficiency level and attributed them to the learners having different cultural backgrounds (Bouton, 1999).

His first longitudinal study (1992) was carried out with thirty of the original subjects who were still on campus four and a half years later. They were retested with the same test battery that had been used in 1986 assuming that the fact that they had already taken this test would have practically no effect on their performance after 4 and ½ years (Bouton, 1992). The results showed that the subjects had made considerable progress, deriving the same message as the NSs did 91% of the time (Bouton, 1999).

Bouton (1994) carried out a second and more detailed longitudinal study. Two more groups of university NNS students were tested with a shorter, modified version of the one used in the 4 and ½ years study. The first group was retested after 17 months and the second one after 33 months. Also, these two groups were compared with a group of Chinese students who had stayed on campus between 4 and 7 years so as to see how much progress could be expected beyond that of the 33 month group. The findings in this study indicated that most of the NNS students’ improvement in their ability to interpret implicatures had been achieved during the first 17 months and from that moment on it was slow (Bouton, 1994). Taking into account that waiting 33 months or more is a long time to acquire this “absolutely and unremarkable conversational strategy” present in everyday interactions (Green, 1989 as cited in Bouton, 1999) Bouton wondered whether instruction in conversational implicatures would accelerate the NNS students’ process for the interpretation of implicatures (Bouton, 1999).

In a later study Bouton (1994) tested whether NNS students’ skill in interpreting implicature in American English could be improved through explicit instruction. The subjects in this study were international students at a university in the USA taking a regular ESL course. They were divided into an experimental and a control group. The latter followed the regular syllabus and did not receive any instruction in implicature.The experimental group received explicit instruction in implicature and they were encouraged to find examples of implicatures outside the classroom and also in their L1.

Both the experimental and control groups were tested before and after the treatment. The same test was administered as a pretest and posttest. It is worth mentioning that the time and materials employed in delivering instruction to the experimental sections were made part of the regular syllabus (Bouton, 1999). He compared the findings in this study with the findings in his previous studies and drew a number of conclusions. He found out that in the case of formulaic implicatures teaching proved to be more effective than mere exposure to the TL culture for 17 months to 7 years, whereas non-formulaic implicatures, which were easily recovered by all the NNS students by the time they arrived in the USA, were resistant to formal instruction. Bouton concluded that the clues present in formulaic implicatures allow for dealing with them as whole sets which students can identify and apply to different contexts. This characteristic distinguishes them from non-formulaic implicatures which, since they are largely idiosyncratic, lack an overall system and consequently do not have a pattern to be taught and learned systematically (Bouton, 1999).

Kubota (1995) replicated Bouton’s study (1994) on the teachability of conversational implicature to EFL students. Her subjects were Japanese EFL learners who had studied English for six or seven years. Her test items included a multiple-choice test and a sentence-combining test in which the subjects had to write conversational implicatures.

The students were divided into three groups: A, B, and C and all of them were given the same pretest. Groups A and B were the two instructed groups and C was the control one, which received no treatment. The teacher explicitly explained the rules concerning conversational implicatures to group A, and group B performed consciousness-raising tasks in small groups to discover the rules. Later, the teacher provided them with the correct answers.

Two posttests were given to the three groups. The first posttest was administered twenty minutes after the instruction and the second one was given one month after the study. The first posttest showed that groups A and B did better than group C and that group B’s scores in posttest 1 were better than group A’s. Groups A and B’s scores on posttest 2 did not vary with respect to the first one. Therefore, the treatments in groups A and B proved to be more effective at inducing a positive learning effect on the subjects than no treatment, at least for a short period of time.

Kasper (2001 as cited in Rose & Kasper, 2001) identified a number of significant differences between Kubota’s replication of Bouton’s study on the teachability of implicature and Bouton’s original study that may explain the dissimilarity of the results. Length of treatment is one of the main differences between these studies. Kubota’s sole treatment lasted twenty minutes, whereas Bouton’s study included six one-hour class sessions. Secondly, Bouton’s subjects were more proficient than Kubota’s and last but equally important, the studies were carried out in different learning environments. Kubota’s subjects were EFL Japanese learners and Bouton’s subjects were international students immersed in the target culture. The ESL learners’ advantages over the EFL learners were that they were not only exposed to implicature types in the classroom but also their opportunities for observation and comprehension outside the classroom were maximised, and the fact that they were encouraged to look for examples of implicatures outside the instructional setting increased their motivation towards the acquisition of the target pragmatic structure.

3. METHOD

The participants involved in this study were twenty-six Argentinian adult students receiving formal classroom instruction in English as a foreign language at a language school in Santa Fe.

The subjects belonged to two intact classes attending level 5. According to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe), at this level the subjects’ language competence corresponds to strong Waystage (A2+). Due to institutional and administrative constraints, it was not possible to assign subjects randomly to the experimental and control groups and also, we could not administer standardised proficiency tests to our subjects. Therefore, we made sure that the population in this study was matched for subject variables as much as possible, and we had to rely on language tests given by the institution. Even though earlier studies have shown that pragmatic competence is not guaranteed by grammatical competence (Rose & Kasper, 2001), we chose this level in order that the interpretation of implicatures was not hindered by their limited language competence.

The mean age in both groups was of twenty-five years in the experimental group and the number of males and females was relatively even. All of them had received formal instruction in English for some years. Since direct exposure to the target language over a considerable period of time has proved to enhance the interpretation of implicatures (Bouton, 1992) and instruction in implicature may have an impact on the results of the study, none of the subjects had stayed in an English-speaking country beyond three months, did not have frequent contact with English-speaking people or studied conversational implicatures before.

While the experimental group (EG) was given explicit instruction in implicature, the control group (CG) followed the regular syllabus and received no treatment at all. Both groups were tested before and after the study.

In order to control extraneous variables, such as teachers’ personalities, teaching styles and methods, and to ensure that the CG did not receive any kind of instruction regarding the use of implicature during the study, one of the researchers taught both groups. This also helped to control that the person who administered the tests was the same. The other researcher observed both the treatment sessions and the administration of the pretests and posttests to record any valuable information that may have arisen and to check that what was planned did not differ from what was actually carried out. Also, to reduce the possibility that fatigue may have a variable effect, the groups selected attended classes at the same time of the day.

A written multiple-choice test (MCT) was chosen as the data gathering instrument to assess our subjects’ performance.The pretest and the posttest tests included sixteen items which consisted of brief descriptions of a situation with a dialogue. Out of the sixteen scenarios, twelve contained an implicature (two instances of each implicature type) and the remaining four were distracters. (Appendices 5 and 11 respectively). The rationale behind the inclusion of distracters in the tests was to disguise the targeted pragmatic structure in both the pretest (MCT1) and the posttest (MCT2) and therefore avoid any practice effect in pretesting (Selinger & Shohamy, 1989).

The scenarios which contained an implicature were based on the scenarios that appear in Bouton and Kubota’s studies. However, since some changes were made to them, we decided to give the modified scenarios to a group of natives to validate the implicatures.The interpretation chosen by most of them was considered to be the expected one.

Our informants were twelve American adults living in the United States. Seventy-five percent were females and twenty-five percent were males and their mean age was thirty-five. They were asked to answer some demographic questions which were meant to test their having a similar socio-cultural background (Appendix 1).

The instrument given to our informants differed from the one we gave to our subjects in that even though the situations were exactly the same, the choices were different. Our informants were given the implicature and were asked to choose its best interpretation whereas our subjects were given a set of possible answers to choose from. This set of choices consisted of: an implicature, two or three direct answers and/or a disjointed option and they were told that there could be more than one correct answer (Appendices 2 and 3).

The main difference between these tests and the tests in Bouton and Kubota’s studies lies in the fact that our subjects were asked to choose the possible response(s) to the conversations rather than the interpretations of the responses. The reason for this change resided in that this kind of instrument would not force our subjects to think pragmatically and therefore focus on implied meaning that they might not otherwise notice. Thus it would truly test their ability to draw non-literal meaning. In order to check their arriving at the correct interpretation of the implicature, once they handed in the test, they had to write the answer to a set of questions if one of their selected choices included an implicature. The rationale behind these questions was to check their full understanding of the implicatures. The experimental and control groups completed both the MCT1 and MCT2 during the same weeks.

Before administering the pretest, both groups were asked to complete a survey questionnaire which consisted of items on students’ personal data, length of stay in an English-speaking country and their contact with native speakers of the language (Appendix 4).

The groups were pretested before the study with the purpose of obtaining both an overview of their pragmatic awareness of implicature and a benchmark against which to measure the progress of the experimental group after the treatment. The MCT1 was administered to all the population in the study one month before the treatment so as to eliminate any pretest effect on the treatment (Takahashi, 2001).

A similar multiple-choice test was delivered as posttest one week after the treatment and it was taken by both the participants in the experimental and the control groups. Despite our being aware of the importance of including delayed posttests to assess the lasting effect of instruction on the subjects, their administration was not possible because some of the subjects were no longer in intact classes during the semester after the treatment and this left us with a reduced number of subjects.

Explicit inductive instruction in implicature was developed to enhance their ability to recover implicatures. It consisted of five treatment sessions which were delivered during general English classes in the experimental group. The sessions lasted approximately one hour each and comprised a three-week period.

Video scenes and handouts composed the treatment material for this study and formed the starting point for the free-flowing discussion which resulted from the presentation of each new implicature type. It also promoted the learners’ development of some generalizations about how the implicature worked.

Even though the textbook and the material that are part of the regular syllabus may have instances of implicature, it was not possible to integrate the instructional treatment with the topics being dealt with in the syllabus at the time of the study.

In the first session the learners were introduced to the notion of conversational implicature as a tool of indirect communication (Appendix 6). The examples used in this session were taken from Grundy (1995). Then, in the second and third sessions they were presented with conversations including the different kinds of conversational implicature addressed in the present study: POPE Q implicature (rhetorical question), Minimum Requirement Rule and sequence-based implicature in the second session (Appendix 7) and indirect criticism, irony, and relevance-based implicature in the third session (Appendix 8). After having been presented with the different types of implicature, in the fourth and fifth sessions the learners were provided with tasks in which all the implicatures were mixed up (Appendices 9 and 10 respectively).

4. RESULT

Data were collected one month prior to the beginning of instruction and one week after instruction by means of two MCTs. They were later analysed statistically. The learners obtained a score of 1 if the implicature was selected and correctly interpreted. If they did not select the implicature or it was selected but they failed to interpret it, they received a score of 0.

To compare how common the phenomenon under study was in the two groups before and after instruction, the frequency for the selection and correct interpretation of each response was obtained.

The mean and the standard deviation for each group were calculated in the MCT1 and MCT2. Also, in order to ascertain that the differences observed between the two groups were the result of the instruction and not due to chance, a t-test procedure was used to analyse the data from the two groups. Applying the t-tests provided us with a t-value that was later compared with a standard table of t-values to determine the statistical significance of the results at the 0.05 level (95% confidence).

Regarding the results of the MCT1, the frequencies of scores of the CG and EG were within the same range (0-40%). It is worth noticing that the majority of the scores fell within the lowest range in both groups (0-10%) and the number of subjects who obtained the same highest mark also coincided. These results indicate that the performance in both groups before instruction proved to be fairly similar.

This is also apparent in the mean scores obtained by the CG and the EG (1.4166, and 1.8571 respectively). The standard deviation shows that the subjects’ performance in both groups was quite uniform (CG=1.1644 and EG=1.1673) and the t-test result confirms that by conventional criteria, the difference between the two mean scores (t =1.7942; p≥.05) is considered to be not statistically significant.

Pretest results indicate that of the twelve items contained in the MCT1 the subjects in both groups were unable to handle POPE Q implicatures and the learners in the CG failed to interpret irony-based implicatures. However, only one subject in the EG interpreted one of the items involving irony. The CG and the EG’s performance regarding relevance-based implicatures was rather poor. They both obtained a score of 0 in one of the items within this implicature type whereas in the other few subjects arrived at its correct interpretation. When we compare the scores of the two groups in implicatures based on the Minimum Requirement Rule, we find that the CG outperformed the EG. On the other hand, those implicatures involving indirect criticism showed the opposite tendency. As regards sequence-based implicatures, even though many learners in both groups recognised them, the EG’s resulting scores were higher.

It is noteworthy that most students in the two groups misinterpreted a high number of implicatures as they took them at face value, failing to infer the implicit meaning. Also a great number of implicatures were left unselected and few of them were retrieved occasionally.

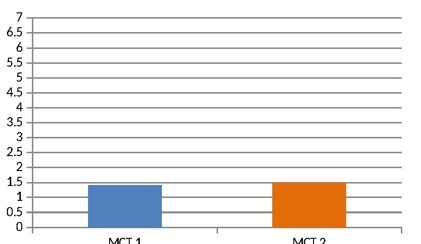

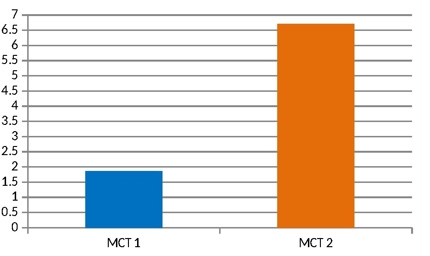

In the posttest, the frequency of the scores in the CG did not display much variation with respect to the pretest since they went down slightly (0-30%). Also, the majority of the scores remained constant (0-10%). Unlike the CG’s posttest scores, the EG’s scores ranged from 0 to 100% and most of the scores fell within the 61-70% range. The distribution of the rest of the scores with respect to this interval was quite uniform. These results clearly show that the performance of the EG was considerably affected by the treatment. The CG’s mean score did not vary much in comparison with the MCT1 (1.5), whereas the mean score for the EG increased significantly (6.7143). This dramatic difference in the subjects’ average performance before and after instruction can be easily visualised in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Mean of CG in MCT1 and MCT2

Figure 2. Mean of EG in MCT1 and MCT2

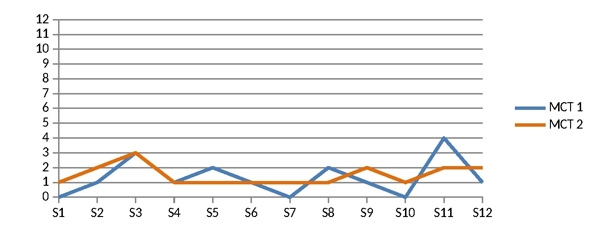

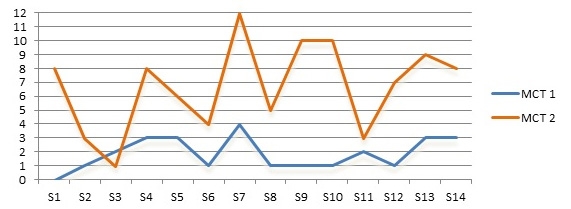

The variability of the scores in both groups also differed in the MCT2 (CG=0.6741 and EG=3.1727) and in the EG in comparison with the MCT1 (1.1673 and 3.1727). It is worth mentioning here that the variability in the EG was considerably greater in the MCT2, indicating that after the instruction the group became more heterogeneous. The t-test result shows that the difference between the mean scores of the two groups is considered to be extremely statistically significant (t= 5.5709; p≤.05). Figures 3 and 4 clearly illustrate the differences in the spread of behaviours among the subjects in both groups in the MCT1 and MCT2 in relation to the mean.

Figure 3. Standard Deviation of CG in MCT1 and MCT2

Figure 4. Standard Deviation of EG in MCT1 and MCT2

The CG’s results in the MCT2 as regards the types of implicatures retrieved remained also quite stable in comparison with the MCT1. None of the subjects in the CG could arrive at the correct interpretation of POPE Q implicatures and the learners exhibited the opposite tendency as regards relevance-based and irony-based implicatures. Relevance implicatures were not selected by any subject whereas one type of irony-based implicature was chosen by only one subject. Implicatures involving indirect criticism were also among the least recognised implicatures. Their performance on the Minimum Requirement Rule and sequence of events showed no significant difference with respect to the pretest.

The EG’s performance in the MCT2 changed dramatically in comparison with the MCT1. There was a meaningful increase in their ability to recognise those implicature types which proved to be quite difficult before instruction, namely POPE Q, Minimum Requirement Rule, irony and relevance. It would be important to mention that with regard to those implicatures which were not troublesome to them in the MCT1, namely sequence-based implicatures, the EG made no dramatic improvement. As regards the implicatures based on indirect criticism they made quite good progress.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The MCT1 scores allowed us to assert that most students in the two groups proved to be rather insensitive to implicatures before the instruction period. Even though their mean scores showed that their overall performance was quite alike, their ability to recover certain types of implicatures differed. The CG was better at recognising Minimum Requirement Rule implicatures whereas the EG was more successful in their recovery of implicatures involving indirect criticism. Regarding the implicatures that were not recovered, most of their misinterpretations corroborate the assumption that EFL learners tend to interpret utterances literally rather than infer the implied meaning, and overlook contextual details (Rose & Kasper, 2001). Therefore, the initial testing suggested that the interpretation of implicatures might be a potential barrier to cross-cultural communication and that it was worth carrying out the treatment.

The results of the MCT2 clearly showed that the EG outperformed the CG. These findings corroborate Bouton’s results in one central aspect: explicit teaching has an undoubted positive impact on the learners’ ability to recover implicatures. However, they differed from Bouton’s in that there was not a clear-cut distinction in the implicatures that demonstrated to be amenable to explicit teaching. While in Bouton’s study the formulaic nature of certain implicatures made them an easy object for instruction, in this study we found that the EG exhibited a significant increase in the interpretation of almost all the implicatures, no matter if they were based on some kind of formula or not. Even though the learners did not make much progress in the interpretation of sequence-based implicatures, there was some improvement.

Regarding the fact that the EG became more heterogeneous after instruction, teaching may have impacted differently on the learners within the group. A possible explanation for this variability in the students’ improvement could be that as Rose & Kasper (2001) assert, the task of understanding implicature is more complex and cognitively demanding in comparison with other target structures since it implies accessing and integrating cultural, linguistic and pragmatic knowledge fast and connecting it with context and textual information. Taking this into account, we consider that the skill of discovering indirect meaning might be an even more complex task than merely choosing the correct interpretation. Accordingly, this skill might take longer to acquire.

Rose & Kasper (2001) assert that language testing influences the content of language teaching and how language is taught. Taking this into consideration, we believe that the instruction could have been even more effective if the subjects in the EG had been told that the target structure under study would be included in their regular tests since they could have been further motivated to learn it.

In summary, the results of this study confirmed the assumption that explicit instruction in implicature can make a difference in a foreign language context. Our learners demonstrated that after instruction their ability to exploit context information improved considerably as they proved to go beyond the literal meaning of the utterances and succeeded in inferring indirectly conveyed meaning.

Given this evidence, together with the importance of implicature as a tool of indirect communication, the restricted opportunities for EFL learners to use the TL outside the classroom, the scarce availability of pragmatic input in the syllabus and their aim to communicate successfully with native speakers, it is undeniable that assisting them with comprehension of implicit meaning will be highly profitable. Therefore, we think that instruction in implicature should be part of any EFL program if its overall teaching and learning goal is communication.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2001) Evaluating the empirical evidence: Grounds for instruction in pragmatics? In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.). Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 13-32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bouton, L F. (1988). A cross-cultural study of ability to interpret implicatures in English. World Englishes, 7, 183-196.

Bouton, L.F. (1992). The interpretation of implicature in English by NNS: Does it come automatically -- without being explicitly taught? Pragmatics and Language Learning, 3, 53-65.

Bouton, L F. (1994a). Can NNS skill in interpreting implicature in American English be improved through explicit instruction? -- a pilot study. Pragmatics and Language Learning, 5, 89-109.

Council of Europe. The Common European Framework of References for Languages (CEFR). Retrieved December, 10, 2011, from http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/cadre_en.asp

Grundy, P. (1995). Doing Pragmatics. London: Edward Arnold.

Hinkel, E. (1999). Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, G. (2001). Classroom research on interlanguage pragmatics. In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching (pp. 33-60). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kubota, M. (1995). Teachability of conversational implicature to Japanese EFL learners. Institute for Research in LanguageTeaching Bulletin,9, 35-67.

Leech, G. (1983). Principles of Pragmatics. New York: Longman.

Levinson, S. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martínez Fernández, B., & Fernández Fontecha, A. (2008). The teachability of Pragmatics in SLA: Friends’ humour through Grice.Porta Linguarum, 10, 31-43.

Niezgoda, K., & Rover, C. (2001) Pragmatic and grammatical awareness: A function of the learning environment? In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.). Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 63-79). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, K., & Kasper, G. (2001). Pragmatics in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, K & Ng Kwai-fun, C. (2001). Inductive and deductive teaching of compliments and compliment responses. In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.). Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 145-170). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Takahashi, S. (2001). The role of input enhancement in developing pragmatic competence. In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.). Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 171-199). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tateyama, Y. (2001). Explicit and implicit teaching of pragmatic routines. In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.). Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 200-222). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yoshimi, D. R. (2001). Explicit instruction and JFL learner’s use of interactional discourse markers. In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.), Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 223-247). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

APPENDIX 1. DEMOGRAPHIC SURVEY: INFORMANTS.

Before doing the task please answer the questions below.

1. What is your age?

2. What is your gender?

3. What is your nationality?

4. What is your primary language?

5. What is the highest level of education you have completed?

6. What is your job?

APPENDIX 2. VALIDATION OF THE INSTRUMENT - PRETEST

Multiple Choice Discourse Completion Test

Implicature types: irony (scenarios 1 and 8), relevance (scenarios 2 and 7), Minimum Requirement Rule (scenarios 3 and 12), indirect criticism (scenarios 4 and 11), rhetorical question (scenarios 5 and 10), sequence of events (scenarios 6 and 9). The correct interpretation of the implicatures present in the different scenarios is indicated by an asterisk.

Please read the following examples and tick the correct response to the question underneath each example.

Example 1:

Bill and Peter have been working together for many years. Now Bill and one of his best friends, who also works at the same company, are talking about what happened at work yesterday after he left the office.

Bill’s friend: Bill, I’m sorry to say this but I heard Peter telling our boss that you were late for work last Tuesday.

Bill: Peter knows how to be a good friend.

Which of the following best says what Bill means?

a. Peter is not acting the way a friend should. *__

b. Peter and Bill’s boss are becoming really good friends. __

c. Peter is a good friend, so Bill can trust him. __

d. Nothing should be allowed to interfere with Bill and Peter’s friendship. __

Example 2:

One morning Frank and Helen were talking outside their house. Frank wanted to know what time it was, but he didn’t have a watch.

Frank: What time is it, Helen?

Helen: The postman has been here.

Frank: Okay. Thanks.

What message does Frank probably get from what Helen says?

a. She is telling him approximately what time it is by telling him that the postman has been here. *__

b. By changing the subject, Helen is telling Frank that she does not know what time it is. __

c. She thinks that Frank should stop what he is doing and read his mail. __

d. Frank will not be able to derive any message from what Helen says, since she did not answer his question. __

Example 3:

Nigel Brown is a dairy farmer and needs to borrow money to build a new barn. When he goes to the bank to apply for the loan, the banker tells him that he must have at least 50 cows on his farm in order to borrow enough money to build a barn.

Banker: Mr. Brown, you have 50 cows, don’t you?

Mr. Brown: Yes, I do.

Which of the following says exactly what Brown means?

a. He has exactly 50. __

b. He has at least 50 cows - maybe more.* __

c. He has no more than 50 cows – maybe less. __

d. He could mean any of these three things. __

Example 4:

Three close friends have to hand in a paper this week. Yesterday Chris wrote the first part of the paper and sent it to Laura and Mike.

Laura: Have you finished reading what Chris wrote yet?

Mike: Yeah, I read it last night.

Laura: What did you think of it?

Mike: I thought it was well-typed.

How did Mike like Chris’s paper?

a. He liked it; he thought it was good. __

b. He thought it was important that the paper was well typed. __

c. He really hadn’t read it well enough to know. __

d. He didn’t like it. *__

Example 5:

A group of students are talking about their coming vacation. They would like to leave a day or two early but one of their professors has said that they will have a test on the day before vacation begins. None will be excused, he said. Everyone had to take it. After class, some of the students get together and talk about the situation, and their conversation goes as follows:

Kate: I wish we didn’t have that test next Friday. I wanted to leave to Florida before that.

Jake: Oh, I don’t think we’ll really have that test. Do you?

Mark: Professor Schmidt said he wasn’t going anywhere this vacation. What do you think, Kate? Will he really give us that test?

Kate: Does the sun come up in the east these days?

What is the point of Kate’s last question?

a. I don’t know. Ask me a question I can answer. __

b. Let’s change the subject before we get really angry about it. __

c. Yes, he’ll give us the test. You can count on it. *__

d. Almost everyone else will be leaving early. It always happens. We might as well do it, too. __

Example 6:

Two friends are talking about what a neighbour of theirs did last weekend.

Rachel: Hey, I heard that Sam went to New York last Saturday and stole a motorbike.

Wendy: Not exactly. He stole a motorbike and went to New York.

Rachel: Are you sure? That’s not the way I heard it.

What actually happened is that Sam stole a motorbike in New York last Saturday. Which of the two has the right story then?

a. Rachel. *__

b. Wendy. __

c. Both are right since they are both saying essentially the same thing. __

d. Neither of them has the story quite right. __

Example 7:

Lars: Where’s Rudy, Tom? Have you seen him this morning?

Tom: There’s a yellow Honda parked over by Sarah’s house.

What Tom is saying is that…

a. He just noticed that Sarah has bought a new yellow Honda. __

b. He doesn’t know where Rudy is. __

c. He thinks Rudy may be at Sarah’s house.* __

d. He likes yellow Hondas and wants Lars to see one. __

Example 8:

Two days ago Tom was invited to a dinner party at Mary’s house. After the meal, Tom realised that they were playing his favourite song in the living room. He went in and saw Sue playing the piano and Mary singing along. Some days later Tom was talking to a friend who couldn’t come the party.

Tom’s friend: What did Mary sing?

Tom: Mary? I’m not sure, but Sue was playing “My Wild Irish Rose.”

Which of the following says what Tom meant by this remark?

a. He was only interested in Sue and did not listen to Mary. __

b. Mary sang very badly. *__

c. Mary and Sue were not doing the same song. __

d. The song that Mary sang was “My Wild Irish Rose.” __

Example 9:

Mr. Rose was murdered at his house. The true story is that the murderer changed his clothes inside the house before escaping. A police officer is in Mr. Rose’s garden conducting the following interview.

Police officer: Mrs. Rose, whose are these clothes?

Mrs. Rose: The murderer’s! Definitely! I saw him changing his clothes and running out of the house.

Mrs. Rose’s son: I thought the man first ran out of the house and changed his clothes.

Mrs. Rose: I don’t remember it that way.

Who said the right story?

a. Mrs. Rose. *__

b. Mrs. Rose’s son. __

c. Both are right. __

d. Neither of them is right. __

Example 10:

Two roommates are talking about their plans for the summer.

Fran: My mother wants me to stay home for a while, so I can be there when our relatives come to visit us at the beach.

Joan: Do you have a lot of relatives?

Fran: Is the sky blue?

How can we best interpret Fran’s question?

a. Fran has a lot of relatives. *__

b. Fran thinks her relatives are all blue. __

c. Fran is new to the area and is trying to find out what the summers are like. __

d. Fran is trying to change the subject; she doesn’t want to talk about her relatives. __

Example 11:

Two women are at a fashionable party. They are wearing beautiful long dresses and expensive dress shoes.

Chloe: Wow, Jane. I love your shoes! They’re wonderful. What do you think of mine?

Jane: They look comfortable.

What does Jane think of Chloe’s shoes?

a. She likes them because they are comfortable. __

b. She doesn’t care about their appearance. What is important to her is that they are comfortable. __

c. She doesn’t like them. *__

d. She is amazed by how comfortable they look. __

Example 12:

Two golfers are talking about their chances in the 95th local university golf tournament.

Fred: What score do you think we will need to enter the tournament tomorrow, Brad?

Brad: Oh, a 75 ought to do it. Did you have a 75? I didn’t.

Fred: Yes, I did.

Which of the following says exactly what Fred means?

a. He had no more than a 75 – maybe less. __

b. He had exactly a 75. __

c. He had at least a 75 - maybe more. *__

d. He could mean any of these three things. __

APPENDIX 3. VALIDATION OF THE INSTRUMENT - POSTTEST

Multiple Choice Discourse Completion Test

Implicature types: irony (scenarios 4 and 7), relevance (scenarios 2 and 8), Minimum Requirement Rule (scenarios 5 and 12), indirect criticism (scenarios 3 and 11), rhetorical question (scenarios 1 and 10), sequence of events (scenarios 6 and 9). The correct interpretation of the implicatures present in the different scenarios is indicated by an asterisk.

Please read the following examples and tick the correct response to the question underneath each example.

Example 1:

A group of colleagues are talking about their coming vacation. They would like to leave a day early but their boss has said that they will have an important meeting on the day before vacation begins. None will be excused, he said. Everyone has to attend it. After work, some of the colleagues get together to talk about the situation, and their conversation goes as follows:

Tom: I wish we didn’t have that meeting next Saturday. I wanted to leave for Canada before that.

Jim: Oh, I don’t think we’ll really have that meeting. Do you?

Bill: Mr. Gordon said he wasn’t going anywhere this vacation. What do you think, Tom? Will we really have that meeting?

Tom: Does the sun come up in the east these days?

What is the point of Tom’s last question?

a. I don’t know. Ask me a question I can answer. __

b. Let’s change the subject before we get really angry about it. __

c. Yes, he’ll have that meeting. You can count on it. *__

d. Almost everyone else will be leaving early. It always happens. We might as well do it, too. __

Example 2:

Liz: Where’s dad, Jane? Have you seen him?

Jane: The TV in the living room is on.

What Jane is saying is that…

a. She just noticed that the TV in the living room is on. __

b. She doesn’t know where their dad is. __

c. She thinks their dad may be in the living room.* __

d. She likes the new TV and wants Liz to see it. __

Example 3:

Three close colleagues have to give a presentation on Monday. Yesterday Susan wrote the first part of the presentation and sent it to Laura and Mike.

Laura: Have you finished reading what Susan wrote yet?

Mike: Yeah, I read it last night.

Laura: What did you think of it?

Mike: I thought it was well-typed.

How did Mike like Susan’s part?

a. He liked it; he thought it was good. __

b. He thought it was important that the paper was well-typed. __

c. He really hadn’t read it well enough to know. __

d. He didn’t like it. *__

Example 4:

Laura and Amy have been classmates for many years. Now Laura and one of her best friends, who also goes to the same school, are talking about what happened at school yesterday after she left the classroom.

Laura’s friend: Laura, I’m sorry to say this but I saw Amy telling our teacher that you were late for class last Monday.

Laura: Amy knows how to be a good friend.

Which of the following best says what Laura means?

a. Amy is not acting the way a friend should. *__

b. Amy and Laura’s teacher are becoming really good friends. __

c. Amy is a good friend, so Laura can trust her. __

d. Nothing should be allowed to interfere with Laura and Amy’s friendship. __

Example 5:

A young couple are in a bank to apply for a loan because they want to buy a new car. The banker tells them that if they both earn $4000 a month, the bank will give them the loan.

Banker: You both earn $4000, don’t you?

Couple: Yes, we do.

Which of the following says exactly what the couple mean?

a. They earn exactly $4000. __

b. They earn at least $4000 - maybe more.* __

c. They earn no more than $4000 – maybe less. __

d. They could mean any of these three things. __

Example 6:

Two friends are talking about what a friend’s cousin did last Sunday.

Peter: Hey, I heard that Bill went to Boston and stole a car last Sunday.

Wendy: Not exactly. He stole a car and went to Boston.

Peter: Are you sure? That’s not the way I heard it.

What actually happened is that Bill stole a car in Boston last Sunday. Which of the two has the right story then?

a. Peter. *__

b. Wendy. __

c. Both are right since they are both saying essentially the same thing. __

d. Neither of them has the story quite right. __

Example 7:

Last weekend Peter went to a restaurant for dinner. After the meal, there was a music show. Some friends of his, Tom and Henry, were the musicians. Tom played the piano and Henry sang together with him. Some days later, Peter was talking to a friend about the show.

Peter’s friend: What did Henry sing?

Peter: Henry? I don’t know, but Tom was playing “New York, New York”.

Which of the following says what Peter meant by this remark?

a. He was only interested in Tom and did not listen to Henry. __

b. Henry sang very badly. *__

c. Tom and Henry were not doing the same song. __

d. The song that Henry sang was “New York, New York.” __

Example 8:

Two sisters have called a taxi because they are going to their cousin’s house to have dinner. They are waiting for the taxi to arrive. One of them asks:

Daisy: What’s the time, Anne?

Anne: Your favourite programme has started.

Daisy: Okay. Thanks.

What message does Daisy probably get from what Anne says?

a. She is telling her approximately what time it is by telling her that her favourite programme has started. *__

b. By changing the subject, Anne is telling Daisy that she does not know what time it is. __

c. She thinks that Daisy should stop what she is doing and watch her favourite programme. __

d. Daisy will not be able to derive any message from what Anne says, since she did not answer her question. __

Example 9:

An old lady, Mrs. Queen, was robbed of some money at her house. The true story is that the thief dropped his mobile phone inside the house before escaping. A police officer is in Mrs. Queen’s kitchen conducting the following interview.

Police officer: Mrs Queen, whose is this mobile phone?

Mrs Queen: The thief’s! Definitely! I saw him dropping his mobile phone and running out of the house.

Mrs Queen’s son: I thought the man first ran out of the house and dropped his mobile.

Mrs Queen: I don’t remember it that way.

Who said the right story?

a. Mrs. Queen. *__

b. Mrs. Queen’s son. __

c. Both are right. __

d. Neither of them is right. __

Example 10:

Two friends have been planning to go on a trip on their own for their winter holidays.

Jenny: My parents want me to go to Córdoba with them to visit our family there.

Susan: Oh, do you think you will have to go?

Jenny: Is the sky blue?

How can we best interpret Jenny’s question?

a. Jenny thinks she will have to go. *__

b. Jenny thinks her parents are blue. __

c. Jenny is new to the area and is trying to find out what the summers are like. __

d. Jenny is trying to change the subject; she doesn’t want to talk about her parents’ plans. __

Example 11:

Two women are at a wedding party. They have both changed their hairstyles.

Sheila: Wow, Kate. I love your new hairstyle! It’s fantastic. What do you think of mine?

Kate: Your hair is very neat. __

What does Kate think of Sheila’s new hairstyle?

a. She likes it because it is neat. __

b. She doesn’t care about how it looks. What is important to her is that it is neat. __

c. She doesn’t like it. *__

d. She is amazed by how neat it looks. __

Example 12:

Two students are talking about their chances of passing an exam at university.

Paul: What score do we need to pass the English exam, John?

John: Oh, a 70 percent ought to do it. Did you have a 70? I didn’t.

Paul: I did. __

Which of the following says exactly what Paul means?

a. He had no more than a 70 – maybe less. __

b. He had exactly a 70. __

c. He had at least a 70 - maybe more. *__

d. He could mean any of these three things. __

APPENDIX 4. DEMOGRAPHIC SURVEY: SUBJECTS.

Before doing the task please answer the questions below. You can answer the questions in English or Spanish.

1. What is your name?

2. What is your age?

3. What is your gender?

4. What is your nationality?

5. What is your primary language?

6. Have you ever been to an English-speaking country?

7. How long did you stay there?

8. Do you keep in contact with English-speaking people? How? How often?

9. When did you start studying English?

10. How long have you been studying English here?

11. What is the highest level of education you have completed?

12. What is your job?

APPENDIX 5. PRETEST (THE UTTERANCE CONTAINING AN IMPLICATURE IS INDICATED BY AN ASTERISK)

Multiple-Choice Test

Implicature types: irony (scenarios 2 and 11), relevance (scenarios 3 and 10), Minimum Requirement Rule (scenarios 4 and 15), indirect criticism (scenarios 7 and 16), rhetorical question (scenarios 6 and 14), sequence of events (scenarios 8 and 12). Distracters (scenarios 1, 5, 9 and 13).

Choose from the options below. There can be more than one correct answer.

1.

Jenny is at a clothes shop and she wants to buy a t-shirt. She asked the shop assistant for a medium.

Shop assistant: I’m sorry we don’t have your size.

Jenny:

a. What a pity!__

b. I hope so.__

c. I’ll take it.__

d. You’re welcome.__

2.

Bill and Peter have been working together for many years. Now Bill and one of his best friends, who also works at the same company, are talking about what happened at work yesterday after he left the office.

Bill’s friend: Bill, I’m sorry to say this but I heard Peter telling our boss that you were late for work last Tuesday.

Bill:

a. Peter knows how to be a good friend.*__

b. Peter is a very good friend, so I can trust him.__

c. I thought he was a nice person. Now I know he isn’t.__

d. I saw them too.__

3.

One morning Frank and Helen were talking outside their house. Frank wanted to know what time it was, but he didn’t have a watch.

Frank: What time is it, Helen?

Helen:

a. It’s 8 am.__

b. The postman has been here.*__

c. It’s 6 pm.__

d. I don’t know.__

4.

Nigel Brown is a dairy farmer and needs to borrow money to build a new barn. When he goes to the bank to apply for the loan, the banker tells him that he must have at least 50 cows on his farm in order to borrow enough money to build a barn.

Banker: Mr. Brown, you have 50 cows, don’t you?

Mr. Brown:

a. I do. *__

b. Yes, I have exactly 50.__

c. No, I don’t.__

d. Yes, I have 20.__

5.

Two friends are saying goodbye.

Tom: See you tomorrow.

David:

a. Good morning.__

b. I can’t see.__

c. OK. Don’t be late.__

d. Hello.__

6.

A group of students are talking about their coming vacation. They would like to leave a day or two early but one of their professors has said that they will have a test on the day before vacation begins. None will be excused, he said. Everyone had to take it. After class, some of the students get together and talk about the situation, and their conversation goes as follows:

Kate: I wish we didn’t have that test next Friday. I wanted to leave to Florida before that.

Jake: Oh, I don’t think we’ll really have that test. Do you?

Mark: Professor Schmidt said he wasn’t going anywhere this vacation. What do you think, Kate? Will he really give us that test?

Kate:

a. I don’t think so.__

b. Yes, for sure.__

c. Yes, we had the test last Friday.__

d. Does the sun come up in the east these days?*__

7.

Three close friends have to hand in a paper this week. Yesterday Chris wrote the first part of the paper and sent it to Laura and Mike.

Laura: Have you finished reading what Chris wrote yet?

Mike: Yeah, I read it last night.

Laura: What did you think of it?

Mike:

a. I didn’t like it.__

b. It was good.__

c. I thought it was well-typed.*__

d. It was awful.__

8.

Two friends are talking about what a neighbour of theirs did last weekend.

Rachel: Hey, I heard that Sam stole a motorbike in New York last Saturday.

Wendy:

a. Are you kidding? I can’t believe it!__

b. Yes, he stole a motorbike and went to New York.__

c. Yes, I heard that too, it’s crazy!__

d. That’s right. He went to New York and stole a motorbike.*__

9.

Two friends are talking on the phone.

Sam: OK. I have to go now. I promise I’ll write a letter to you as soon as I get home.

Ruben:

a. Let me post it.__

b. That will be nice.__

c. It hasn’t come yet.__

d. I’m looking forward to it.__

10.

Lars: Where’s Rudy, Tom? Have you seen him this morning?

Tom:

a. He’s in Sarah’s house.__

b. No, I haven’t.__

c. Ok, see you.__

d. There’s a yellow Honda parked over by Sarah’s house.*__

11.

Two days ago Tom was invited to a dinner party at Mary’s house. After the meal, Tom realised that they were playing his favourite song in the living room. He went in and saw Sue playing the piano and Mary singing together with her. Some days later Tom was talking to a friend who couldn’t come to the party.

Tom’s friend: What did Mary sing?

Tom:

a. “The True Lover’s Farewell.”__

b. Yes, I loved it!__

c. Mary? I’m not sure, but Sue was playing “My Wild Irish Rose.” *__

d. Would you like to come with me?__

12.

Mr Rose was murdered at his house. The true story is that the murderer changed his clothes inside the house before escaping. A police officer is in Mr. Rose’s garden conducting the following interview.

Police officer: Mrs. Rose, whose are these clothes?

Based on the true facts, Mrs. Rose answers:

a. They must be the murderer’s because I saw him changing his clothes in the living room.__

b. The murderer’s! Definitely! I saw him changing his clothes and running out of the house.*__

c. Which clothes?__

d. After the shot, the murderer left the house immediately and changed clothes. I’m sure they are the murderer’s.__

13.

Susan is planning a trip. She meets her sister and invites her to come.

Susan: I’m going to go to London on Saturday. Would you like to come?

Sister:

a. Me too.__

b. Fine, do we need to book tickets?__

c. I’d love to.__

d. Yes, I have to work on Saturday.__

14.

Two roommates are talking about their plans for the summer.

Fran: My mother wants me to stay home for a while, so I can be there when our relatives come to visit us at the beach.

Joan: Do you have a lot of relatives?

Fran:

a. Is the sky blue?*__

b. Yes, I do. __

c. No, thanks. __

d. I do too.__

15.

Two golfers are talking about their chances in the 95th local university golf tournament.

Fred: What score do you think we will need to enter the tournament tomorrow, Brad?

Brad: Oh, a 75 ought to do it. Did you have a 75? I didn’t.

Fred:

a. I did.*__

b. No, I didn’t.__

c. No, I had a 60.__

d. Yes, I had a 95.__

16.

Two women are at a fashionable party. They are wearing beautiful long dresses and expensive dress shoes.

Chloe: Wow, Jane. I love your shoes! They’re wonderful. What do you think of mine?

Jane:

a. They’re beautiful.__

b. It doesn’t matter.__

c. They look comfortable.*__

d. I can’t wear them any longer. They are way too uncomfortable for me.__

GLOSSARY

1. What a pity: informal expression used when you are sad about something.

2. trust: believe in someone.

3. postman: a person who delivers post.

4. barn: a big building where farm animals are kept.

5. loan: money you borrow from the bank.

6. excused: justified.

7. wish: desire something that probably will not happen.

8. hand in: give something to someone.

9. well-typed: typed without mistakes.

10. post: send via the postal system.

11. park: leave a vehicle in a place temporarily.

12. realize: have knowledge of something.

13. shot: the firing of a gun.

14. roommate: a person who occupies the same room as another.

15. relative: a person in the same family.

16. tournament: competition.

17. ought to: should.

Follow-up questions

1. If you have chosen 2.a, what does Bill think of Peter?

2. If you have chosen 3.b., what is Helen trying to say?

3. If you have chosen 4.a, how many cows do you think he has?

4. If you have chosen 6.d, what does Kate mean?

5. If you have chosen 7.c. how was Chris’s part?

6. If you have chosen 8.d, what did Sam do first?

7. If you have chosen 10.d., what does Tom mean?

8. If you have chosen 11.c., what is Tom trying to say?

9. If you have chosen 12.b, what did the murderer do first?

10. If you have chosen 14.a, what does Fran mean?

11. If you have chosen 15.a, what score do you think Fred had?

12. If you have chosen 16.c, what does Jane think of Chloe’s shoes?

APPENDIX 6. INSTRUCTION: SESSION 1 – STUDENT’S WORKSHEET

1. Look at the following sentence and in pairs invent a short conversation in which this sentence is used. Please explain where it occurs and who the participants are.

It’s the taste.

Imagine the following situation:

A man is sitting in the living room watching TV. A few minutes later, his daughter comes home from school and after saying hello very quickly to his father, she runs to the kitchen, takes some biscuits and starts eating them desperately. Afterwards, her father asks:

Father: Why didn’t you eat your school dinner?

Daughter: It’s the taste

Does it mean the same as in the conversations you provided before? How is the taste in this case?

Imagine that you and a friend of yours are talking about your favourite football team. For example: Manchester United, which is, as you know, one of the most popular teams in England. When he/she asks you how your team played the night before, you answer: They won. What do you mean?

THEY WON

APPENDIX 7. INSTRUCTION: SESSION 2 - STUDENT’S WORKSHEET

1. Look at the conversation below, which illustrates one kind of implicature.

Paul and Georgette are talking about a mutual friend who is always late.

Paul: Do you expect Sheila to be late for the party tonight?

Georgette: Is the Pope Catholic?

• In pairs answer the following questions:

o What is the answer to Georgette’s question?

o Is there any other possible answer to her question?

o What do you think is the answer to Paul’s question then?

o What do you think Georgette means?

2. Now read the following conversation, which contains another kind of implicature.

John is a doctor and wants to apply for a scholarship to study abroad. The secretary at the

university where he wants to study tells him that he must have at least one PhD in order to apply for the scholarship.

Secretary: So John, you have a PhD, don’t you?

John: I do

• Answer these questions:

o What does the secretary want to know?

o Does he have a PhD?

o Do we know how many PhDs he has?

o Is it possible that he, in fact, has more than one PhD?

3. Look at the example below, which illustrates another kind of implicature.

A: I haven’t seen Louise this week. Have you?

B: No. But I heard Jack drove to Chicago and met her.

• Answer the questions below:

o Where did Jack meet Louise?

o How do you know?

o What did he do first: going to Chicago or meeting Louise?

o What does the word AND (which connects both actions) mean in this example? Can you think of a synonym?

o Does AND always mean this?

APPENDIX 8. INSTRUCTION: SESSION 3 - STUDENT’S WORKSHEET

Read the following conversations and tick the possible answer(s).

1)

Context: Phoebe is clearing stuff out of her apartment to make room for her husband, Mike. She decides to get rid of some artwork she has created, and tries to give it to Monica, who has been pretending to like it.

Setting: Monica's flat. Phoebe enters carrying her picture of Gladys. Monica and Rachel are sitting on the couch.

Characters: Phoebe, Monica and Rachel.

Text:

Phoebe: Well, Gladys say hello to your new home!

Monica: Oh, my!

Rachel: Oh, she’s so nice…

a. and big!

b. I have never seen her before.

c. you made her with plastic, cloth and glass. Where did you get those materials?

d. I made her.

2)

Context: Phoebe and Mike, stunned by the expenses involved with a wedding, decide they'll get married in City Hall and give the money to charity. Once they donate it, Phoebe changes her mind and they ask for it back. But Phoebe is still unsure.

Chandler and Monica want to adopt a child. The adoption agency sends a woman (Laura) to evaluate Chandler and Monica and their home.

Setting: Monica and Chandler’s flat.

Characters: Phoebe, Monica and Chandler.

Text:

Phoebe: It’s OK, it’s OK. I made my decision. What I really want is a great big wedding.

Monica: Yay!

Chandler: But you already gave all your money to charity!

Phoebe: Well, I’ll just ask for it back!

Chandler: I don’t think you can do that!

Monica: Why not! This is her wedding day, this is way more important than some stupid kids!

Chandler:

a. Monica, don’t be so cruel.

b. Check it out!

c. That’s sweet, honey, but save something for the adoption Lady.

d. Not his!

3)

Context: